Jumia: How to Build an Ecosystem

I’ve been very reflective lately. It’s been a bit over 5 years since I got into this tech entrepreneurship thing, and recently, I’ve had the headspace to think about how I got...

Filter by Category

I’ve been very reflective lately. It’s been a bit over 5 years since I got into this tech entrepreneurship thing, and recently, I’ve had the headspace to think about how I got...

In February, I observed the Nigerian presidential and governorship election week from Bangladesh. Bordering India and Myanmar, Bangladesh is the world’s eight most populous and...

The industry needs technology providers, asset accreditors (like Fitch for credit), compliant but open exchanges (till the decentralized future is realized), etc.

It will take a lot of privilege for the average Nigerian kid to be able to compete at all as the current pace of the world’s evolution.

The only way cryptocurrencies will threaten the legacy financial system is if they remain and thrive outside of it.

We didn't expect our lives to change immediately, but we expected ordinary miracles. A miracle, in Nigerian terms, would simply be to do something right.

If Harvard admitted students based on the applicant scoring in the top decile of test scores + HS performance, they'll barely admit black people.

My objective is to relentlessly grow our brand to be the biggest non-cash value transfer platform in Nigeria and Africa at large.

Across the world, there are hundreds of millions of immigrants and travelers like me that need to transfer some immediate, non-cash value internationally, but the systems that have been set up to facilitate that don’t take into account the nature of transfers.

My answer here: There are 1.2 billion people in Africa. There will be 2.4 billion by 2050 and that’ll be a quarter of the world’s population. Over the next few decades, not many...

I’ve been very reflective lately. It’s been a bit over 5 years since I got into this tech entrepreneurship thing, and recently, I’ve had the headspace to think about how I got here. This might be lengthy:

I grew up with a fair awareness of technology (see earlier blog post) and as a young kid in Abeokuta, I had the knack for entrepreneurship. I ran a 60-bird poultry farm, a fish pond, and a snail bed as a teenager and almost dedicated an entire gap year after secondary school to it. However, a series of random events led me to enroll at the University of the West Indies, Barbados in 2007 to study Management.

The small Island of Barbados punches well above its size. It has one of the better economies in the Caribbean, hosts a great campus of the region’s most prominent University, and it has a pretty massive offshore financial industry. I happened to be starting college during a major event in world business: the so-called global financial crisis. With its cultural ties to Europe, geographical proximity to the US, and the natural economic dependence on prosperity in those markets, activity in Barbados was buzzing. I found myself, an 18-year old African kid with international exposure limited to satellite TV, in the middle of something exciting somewhere cool. My faculty launched a new double major programme in Accounting and Finance, and because I had good first-semester grades, I was allowed to switch majors. I thought then, wisely, that there was no better time to be studying Finance than in the middle of the global financial crisis.

I obsessed over the subject and thought I’d found my calling for sure. I studied hard, spent my time debating capital structures with Professors, co-founded the Accounting Student’s Association and became the “Director of Educational Resources”, won election as the Accounting, Banking and Finance representative at the Student Guild, etc. I tutored the subject on the weekends and just generally prepared myself for a career in the industry, preferably in a Big-4 accounting firm. In fact, I was already well on their radar with several engagements with the ACCA, CMA, ICAB and Big-4 firms in Barbados.

Presenting to a First Caribbean International Bank Panel, 2011

2010

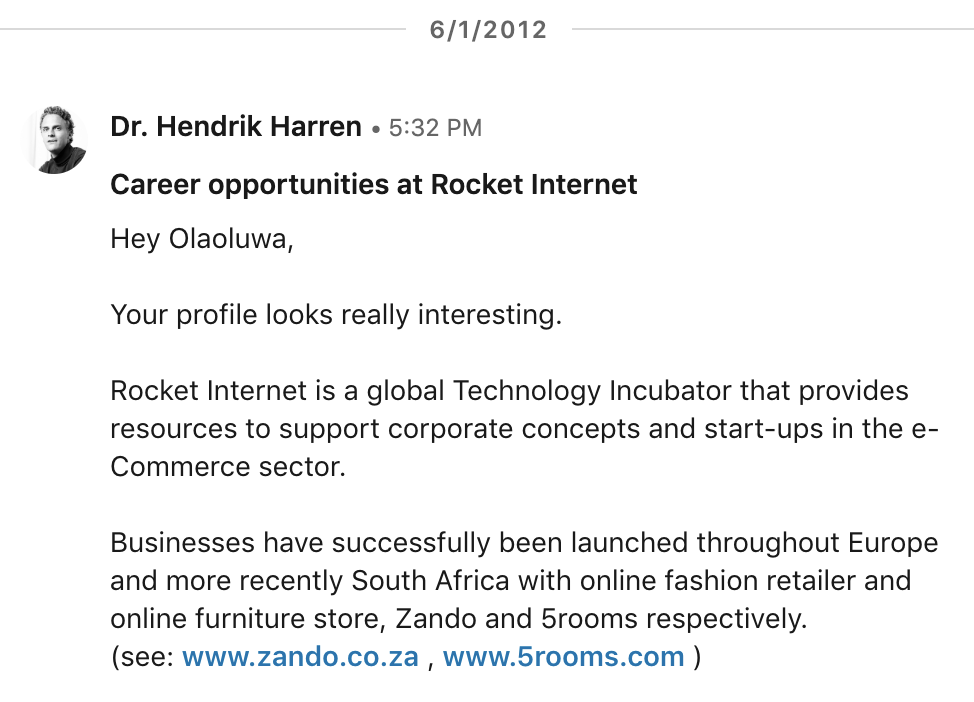

I returned to Lagos Nigeria in 2012 out of a probably misplaced patriotic zeal, updated my Linkedin, cut my hair, borrowed a suit, applied and secured a position at KPMG and went off to complete the mandatory National Youth Service at the University of Benin. All was going according to plan, then I got a Linkedin message.

From my time in Barbados, I was already familiar with e-commerce because I frequently ordered stuff from Amazon. It was just a concept that was very foreign to Nigeria and I was very skeptical it could work. I’m sure there were a number of online shops in 2012, and companies like Wakanow already launched, but none was mainstream for general merchandise and I wouldn’t have imagined ordering anything online in Nigeria at the time. The messaged looked scammy for sure, but I Googled Rocket Internet, found their Wikipedia page and they seemed credible and interesting. I wasn’t looking for a job, but I thought the whole idea was fascinating enough to at least investigate, so I engaged Hendrik, and I was immediately scheduled for an interview in Lagos. The speed was incredible.

The interview was at the “office” in a 4-bedroom house in Lekki. It was nothing like the structured spaces at KPMG. The supposed company was a “Kasuwa.com” and there was definitely no system there. I counted a motley group of maybe 10 people in casual wear, and I was taken up to a make-shift interview room. My interviewer was Babafemi Lawal (my co-founder now at SureGroup). He asked me a few questions I don’t remember, then he stepped out for the MD, Tunde Kehinde. Tunde must have been about 28-29 then and he looked like it. I’d read up about him and knew that he was fresh off a Harvard MBA, so I was expecting a smart-ass interview. I think the interview lasted about 5 minutes. He asked me what I studied and then asked what the relationship was between the Income Statement and the Balance Sheet. I wasn’t about to screw up that question, so I said what needed to be said. An offer came in soon after and against the counsel of people looking out for me, I accepted and was scheduled to resume exactly a month after Hendrik’s Linkedin message.

The Kasuwa experience was WILD. There were between 20-30 people in the madhouse with a few German and French expatriates from Rocket Internet, and there was no job description. Raphael, the co-MD spent half his time answering customer service phone lines, there were barely any supplier relationships, so we were buying anything anywhere at whatever price to sell online. Everything from customer service tracking to order processing to website content was managed on Excel, and as the “Financial Analyst”, my job was mostly to get pretty good at using Excel and churn out all sort of reports.

No one really knew how to do it, but everyone was super keyed into what needed to be done. There were no breaks, e-mails flew around at 3am with slightly fewer expletives as you’d have heard earlier in the day from the expatriates. When the power went off, we moved our laptops to cafes around Lekki till they kicked us out. Everyone was extremely smart, tempers flared, there was a ton of money to spend from Germany, and all we had to do was grow, dammit.

We did grow and fast. With the volume of money we were burning and the quality of people on the job, we had no choice. From 20 to 100 to 200 people every other month and as many orders per sub-category daily, a second building was rented down the road to separate the Fashion business (Sabunta.com) from the General Merchandise business (Kasuwa.com). With more people, seniority and specialization came fast. From Financial Analyst to Pricing Analyst to Senior Financial Analyst to Commercial Planner to Business Intelligence, I held several positions that pretty much just tracked my growing understanding of the business, but mostly my proficiency with Excel and data.

The Commercial Planner role had me in charge of a few categories (Children, Books, Groceries & Drinks), and with guidance from Germany and with the work of Category Managers, my job was to do everything to make sure today’s sales beat yesterday’s, using data. Very soon, you learn that putting a Chimamanda title beside an Obama title will boost the sale of an Achebe title if it’s on the far end to the right, or pricing a breast pump higher will sell it faster (things like that). In those early days, Jeremy Hodara and Sacha Poignonnec, the big bosses at Rocket would fly in, put pressure on everyone at the office, and literally march us to the Mall to show us what merchandising means. They’ll point at something and yell: “Do you have that? Why not? Are you cheaper than that? Do you know why the condoms are placed there?”. It forced us to live and breathe digital commerce, imbibe German-level thoroughness and compete not only online with Konga, but also offline. The competition and pressure were good for us.

The most exciting thing for me, however, was the opportunity to work on initiatives that are mainstream now, but ground-breaking then. For example, setting up a shipping matrix for the heart-stopping moment when we first had to start charging for delivery, or creating a cash-on-delivery model, or thinking through modalities for a fulfillment center, or coordinating the campaign for the first Black Friday. For a 22-year old on his first job, it was a lot of responsibility, and I was paid way above market for only one year into the workforce.

When I met with the partner at KPMG later to discuss why I didn’t want to take up the role, Jumia had already made some noise in the market, and while he was skeptical of the decision, he was understanding, nonetheless.

Kasuwa and Sabunta merged into Jumia, suddenly, every company in Nigeria seemed to be awake to e-commerce. The government came knocking with their usual problems, the banks opened their e-commerce departments, several other niche online stores launched, and Jumia employees were hot cakes (I remember consulting for SLOT’s e-commerce project back then). Offers flew into the inboxes. Konga was competing fiercely. They raised some money and poached some staff. It was a >1,000 people operation with warehouses and delivery vehicles everywhere and millions of Dollars being burned every month. Jumia launched in Kenya, Morocco, and Egypt, and we were frequently on calls with the teams there to share templates.

Things went from zero to a hundred really quickly within a year, then I was contacted by a Jumia employee who had left early to join another company called Venture Garden Group (VGG). VGG was very young then as well, about 2-3 years old. The co-founder, Bunmi Akinyemiju had recently moved to Nigeria from the US to set up a technology business but in the B2B/B2G space. The central VGG idea was to use transparency and automation of data to address payment issues, particularly in government. I met with Bunmi casually at the Southern Sun Hotel, and he sold his dream to me and offered me a pay cut to join the team. I felt I’d grown too fast at Jumia, the idea of building with locals resonated with me and I also wanted to see if I was as good as I thought I was in a new environment, so, I resigned at Jumia on good terms and with huge respect for what we’ve built and joined VGG as some sort of mercenary in the Finance team from that crazy Jumia company.

I brought the same obsession into my work at VGG. It was itself a pretty different and revolutionary company, and I transitioned well into it. I’d already caught the entrepreneurship bug though, and I had data from Jumia showing a significant gap in the market. While at Jumia, I attempted to launch a corporate digital gift card program. I was empowered to run with it and I found somewhat positive reception from potential business customers on an exploratory trip to Ibadan. We couldn’t really push the program though because it was a bit different from the core business of selling merchandise. It needed its own dedicated attention. Oye (my co-founder at SureGroup) was in charge of Marketing Business Intelligence, Babafemi was in charge of Operations Business Intelligence, and I was in charge of Production and Purchasing Business Intelligence, so between the three of us, we had all the data on emerging e-commerce gifting patterns.

At about the same time I resigned, Oye was poached into the newly-formed e-commerce department at UBA, but about 6 months after, in January 2014, we all decided to build Nigeria’s pioneering digital gift card company, and we called it SureGifts. The only problem was that no one knew what gift cards were. More than 9 in 10 people thought gift cards were greetings cards, and shopping vouchers were discount codes like the ones you use on Jumia. Foolishly, we concluded that it was similar to the ignorance about online shopping in 2012 and we’ll just educate the market like Jumia.

I told Bunmi I was leaving to start a company. Bunmi thinks non-traditionally, so he wrote me a first 2m Naira check for some equity, kept my VGG e-mail active and kept us close. Since 2014, I’ve worked with Bunmi and the team on the side in setting up and administering Greenhouse Capital, investing in some of the most promising ventures out of Nigeria.

SureGifts was much tougher than we anticipated. Never underestimate the power of money in the entrepreneurship journey. However, I attribute a lot of our survival DNA to our time at Jumia. Jumia gave us the technical understanding of the e-commerce business, good initial branding, a strong network, a pool of talent to harness, and support. Jumia itself was our first major partner merchant at SureGifts, and at least 8 people that have passed through the SureGifts team have been Jumia ex-employees.

Most of the first 50 people in the Jumia team will have very interesting (positive or negative) stories about their time at Jumia, but what is consistent is the propelling rubberstamp and knowledge that the company has given everyone.

I had someone scour Linkedin for information about the founding team at Jumia (see spreadsheet here); what they were up to before and what they’ve been up to since, and I’m immensely respectful of what they’ve made of themselves, attributable in some part to their time at Jumia going by the trajectory. It’s no surprise at all that 33% of the earliest people have gone on to found their own companies, from Tunde and Ercin at Ace and Lidya, to Evans at Cregital to Chioma at AccountingHub to Raphael at Supermart to Wezam at PrepClass to Sanmi at All Shades Covered to Onyeka at Farmcrowdy to Michael & Moyo at Busha (also ex-SureGifts) to Ochijie at Christopher’s & Co and even Adekunle Gold in the music industry, we’re all hustling it out there. All the other early team members have either maintained senior management roles at Jumia or are at the top of their fields at other major companies. Jumia Nigeria currently lists nearly 2,500 employees on Linkedin.

I’ve been studying Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship at the London School of Economics, and I’ve observed a very shallow view of what impact is, and the sanctimonious ideology around how and where to channel impact-seeking capital. My personal thesis is that, in a market like Nigeria where poverty and economic inactivity is endemic, the biggest downstream impact will be derived by simply building businesses that have the potential to scale, create economic activity and wealth, regardless of what the business is about. Too often, players in the market are looking for cosmetic solutions to specific problems, most of which will be addressed in the long term if more big businesses are built. The likes of Jumia, Konga, Interswitch, Hotels.ng or VGG won’t be classified as your traditional African social enterprises, but in a market like Nigeria where most people are just simply poor, and most of their problems are a consequence of that poverty, any business is social, and the bigger the business, the bigger the social impact. Even as small as we are at SureGifts, three of our former employees have become entrepreneurs (Moyo and Michael at Busha.co and John at Wallet.ng), and as Bunmi did for us, we’ve supported them.

I have my personal grumbles about Jumia (and Konga and Interswitch and everyone) and there have been fallouts with ex-colleagues here and there; regardless, whatever the sentiments, it’s hard to discount the impact of the $767m invested in the business over the past 7 years, and it’s difficult not to appreciate the talent of the people that built the African e-commerce industry as we know it today: The Jumia Mafia (without the money, HA!).

In a few days, Jumia will be executing an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange, seeking a $1.2bn valuation to officially become a unicorn. It might not be Africa-owned, but in an undeniable way, it’s Africa-built, and for that, I am proud and wish them well. For me personally, whatever the future holds for the company, I owe a lot of my personality today to my history at Jumia, and to me, it is already a success story; an African unicorn.

Banner Image by Reuters Luc Gnago (culled from Business Insider)

Be notified when a new post is up!

Comments

This is educative and inspiring.

Awesome read! I’m very proud of you.

Awesome read!!

[…] Source: […]

Inspiring

Well Done Chief. It was an amazing pleasure and privilege to have met and engaged with you.

Good work.

This is great! Awesome experience!

[…] five to about 50 people. Someone made a list of Jumia’s first 50 employees; we suspect it was Olaoluwa Samuel-Biyi, ex Jumia employee and Director, […]

[…] five to about 50 people. Someone made a list of Jumia’s first 50 employees; we suspect it was Olaoluwa Samuel-Biyi, ex Jumia employee and Director, […]

Great one. The Barbados experience was a good opportunity and a foundation. We have a lot of smart people in this country and you just proved that.

Awesome experience!

Awesome experience!

Excellent writing.

Jumia experience most times builds entrepreneurial spirit in us and that pushes everyone to go all out contributing our quota to entrepreneurial ecosystem of Nigeria.

Great read!

Your work ethic and diligence is quite admirable. However, I’m not sure there’s much to boast about companies burning through investor cash with little or no hope of profitability in sight, while looking forward to acquisitions as exits.

[…] five to about 50 people. Someone made a list of Jumia’s first 50 employees; we suspect it was Olaoluwa Samuel-Biyi, ex Jumia employee and Director, […]

I couldn’t refrain from commenting. Very well written!

Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

[…] ‘Laolu Samuel-Biyi […]

[…] five to about 50 people. Someone made a list of Jumia’s first 50 employees; we suspect it was Olaoluwa Samuel-Biyi, ex Jumia employee and Director, […]

[…] Laolu Samuel-Biyi had authored an authoritative first-person account of his time at Kasuwa and Sabunta which would later be part of JUMIA Nigeria, pretty much sounded […]

[…] Laolu Samuel-Biyi had authored an authoritative first-person account of his time at Kasuwa and Sabunta which would later be part of JUMIA Nigeria, pretty much sounded […]

[…] five to about 50 people. Someone made a list of Jumia’s first 50 employees; we suspect it was Olaoluwa Samuel-Biyi, ex Jumia employee and Director, […]

3charleston